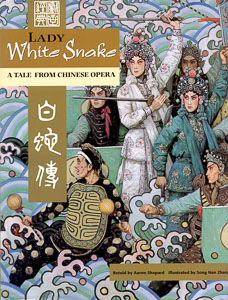

Here is one section of the author note from my picture book, Lady White Snake: A Tale From Chinese Opera. (The other section was on the story.)—Aaron

Imagine you are sitting in a theater, listening to a heroine sing longingly of her beloved. Suddenly the stage is invaded by two bands of acrobatic warriors. They tumble and twirl, cartwheel and somersault, flip this way and that. From the orchestra come sounds of cymbal, gong, and clapper to punctuate the action.

Swords clash, and warriors duck and dodge the blades. Spears fly, only to be hit or kicked back to the thrower—one, two, even four at a time. And what’s this? The heroine has grabbed a sword to join the fight!

Welcome to the world of Chinese opera.

Actually, the word “opera” only begins to describe this pinnacle of China’s traditional performing arts. Like opera in Western countries, Chinese opera features acting, singing, and sumptuous costumes. But it also offers dance, mime, face painting, and acrobatics.

Chinese opera evolved from the earliest Chinese dramas in the twelfth century. Over time, various stage arts were added and integrated until Chinese opera emerged as the country’s most popular entertainment. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, acclaimed opera actors were China’s superstars.

But Chinese opera suffered gravely during China’s Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), when it was almost completely banned, and since then has found itself eclipsed by modern forms of entertainment. Still, it survives today as a “classical” art, honored and appreciated for its place in China’s traditional culture, as well as enjoyed for itself.

Chinese opera is a tradition with many branches. The best-known is Beijing Opera (or Peking Opera, in the older spelling) performed throughout China as well as overseas. But there are also over 300 regional operas, much alike in stage technique, costume, and stories performed, but differing in music and dialect.

Here is a look at some key aspects of Chinese opera.

The stories. There are over 1200 stories used in Chinese opera, mostly drawn from historical legend and mythology. Many promote traditional Chinese values like respect for parents, female modesty, and obedience to authority, while others encourage resistance to injustice or show women in unusually strong roles. For example, female generals are much more common in Chinese opera than in Chinese history.

At least until modern times, audiences were already familiar with the stories they saw performed, so they did not need to see an opera from beginning to end to understand it. For this reason, a traditional performance might be made up only of favorite scenes from one or more operas.

The characters. Each character in a Chinese opera is based on a standard role type, which is recognized at a glance by costume, makeup, and demeanor. This lets the audience know much about a character from the moment the actor comes onstage.

Among the female role types are the young lady, the lively girl, the refined woman, the older woman, and the military woman. Male role types include the young man, the older man, and the military man.

A special group of role types is the “painted faces”—male characters whose strong and simple personalities are represented by mask‑like face painting. This group can include heroes, villains, generals, gods, and demons. (For more about them, see the section below on makeup.) Another special group is the clowns, both male and female, who provide humor through foolishness or wit.

The actors. An actor in Chinese opera is trained especially for one role type and will generally stick to it throughout his or her career. The choice is based on body type and abilities rather than age. For instance, a young male actor might always portray older men.

Until modern times, it was illegal in China for males and females to perform together. So, just as in Shakespeare’s England, female roles were performed by men, who imitated female movements and sang falsetto. Today female roles are almost always played by females, but actresses still copy the voice and movement styles of their male predecessors.

Because of the many skills and the physical agility needed by opera actors, training must begin in childhood. Special schools in China offer this training along with general education.

The stage. The oldest form of the Chinese opera stage is a square platform of bamboo and planks, with the audience on three sides. Corner poles hold a canopy overhead, while a rug or mats cover the floor. An embroidered curtain stretches across the back, with two flaps for the actors to enter and exit. There is no curtain in front, no scenery, and no large props besides a table and chairs.

This kind of stage was designed to be portable, so an opera company could assemble it quickly in a public square or wherever else needed. Permanent opera stages were sometimes built in teahouses, palaces, and temple courtyards, but the basic design was the same.

This century, though, has brought many changes to Chinese opera. Performances today are commonly on Western-style stages with a curtain in front, painted scenery, electric lighting, sound amplification using body mikes, and subtitles projected on screens.

Mime and small props. Lacking scenery and almost any large props, traditional Chinese opera turned instead to the art of mime, often with hand‑held props to aid the illusion. A walk in a circle can mean a long journey. A tasseled whip can become a rider’s horse. Several actors swaying together while one handles a paddle can portray a boat ride.

A table with chairs can become a sitting room, the emperor’s court, or with a chair on top, a mountain to climb. A lantern in hand tells of night and darkness. A dance with blue flags means a flood, or with red ones, a fire. In such ways, Chinese opera portrays much that is not easily shown in realistic theater.

Dance, acrobatics, and other movement. While mime is one type of movement important in Chinese opera, another is dance. Some characters may dance almost constantly as they sing or speak. But even when actors aren’t dancing, their steps and gestures are more or less stylized and dance‑like. In fact, gesturing and even walking are considered arts in themselves.

One of the most popular features of Chinese opera is its acrobatics. All actors are trained in it, but it is the specialty of those who portray battle scenes. In these scenes, it is combined with stage fighting skills such as swordplay and kung fu.

This fighting, though, is stylized rather than realistic. No one dies onstage, and serious wounds are unlikely from spears tipped only with red ribbon. The attraction for the audience is not an illusion of violence but the incredible physical skills and interplay of the actors.

Costume. Chinese opera costumes are colorful, lavish, extravagant—a visual feast. Actors might wear richly embroidered coats, ceremonial robes, or full armor, along with elaborate headgear. Based loosely on fashions of several centuries ago, these costumes are not really meant to represent any historical period, or even to suggest a time of year. Instead they serve as pageantry and also to signal the character’s age, social position, and personality.

Some costume elements are purely for show. For instance, young leading characters commonly wear “water sleeves”—lightweight white extensions of their regular sleeves that trail as low as the ground. These can flow gracefully at full length, or with a few flicks of the wrists fold back to expose the actor’s hands. Warrior helmets are often graced by two pheasant feathers rising high, while armor is often augmented by four pennants jutting out from the back. Both additions create impressive effects during acrobatics.

Makeup. Among the most striking features of Chinese opera is the mask‑like face painting of the “painted face” roles. The colors are bright—red, purple, black, white, blue, green, yellow—and are most often combined two or more in a complex pattern. As with costume, the purpose is both to appeal to the eye and to tell about the character. The colors represent strong personality traits—for instance, red for heroism, white for villainy. Some patterns identify particular characters or animals.

Most other actors make up their faces with white powder, plus rouge to highlight the mouth, eyes, and eyebrows. Male clowns announce themselves with a patch of white paint around the nose and eyes.

Music. The music in a Chinese opera is based on one or more standard melodies arranged to fit that opera. These melodies generally come from local musical tradition, and so will vary from one regional opera to another. Beijing Opera has drawn from a number of regional operas for its own large stock of melodies.

Traditionally, the music is played by six or seven musicians who sit in a back corner of the stage, in full view of the audience. Their instruments include traditional Chinese varieties of the fiddle, the banjo, the guitar, the flute, and the oboe, plus drums, gongs, cymbals, and a wooden clapper. The musicians interact closely with the actors, not only accompanying songs, but also punctuating the action and the dialog with percussion, much as in an American circus.

Today, when a stage is Western-style, the musicians sit instead in the wing or in the orchestra pit. And their instruments might now include others from both China and the West—even an electric guitar!

For more about Chinese opera, you can read Chinese Opera: Images and Stories, by Peter Lovrick, photos by Siu Wang‑Ngai, UBC Press, Vancouver, and University of Washington Press, Seattle, 1997; and Peking Opera, by Colin Mackerras, Oxford University Press, Hong Kong, 1997. Much on Chinese opera can be found by searching the World Wide Web. You might also look for Chinese opera videos at your library or at Web sites of Chinese video suppliers.